Though feminism and Marxism as frameworks divide the population in different ways, and therefore approach artistic analysis differently, the two concepts have much in common as each focuses on institutional marginalisation in society. While much can be obtained from a film using one method alone, utilising both can reveal a deeper relationship between the two power structures of patriarchy and capitalism via intersectionality – in this case, through analysing Hayao Miyazaki’s Oscar-winning animated classic Spirited Away.

The use of a female protagonist in the prepubescent Chihiro is unusual in film; no movie in the top ten highest grossing worldwide the year that Spirited Away was released featured a sole female protagonist. This signals Miyazaki’s subversive approach, and that the film may actively acknowledge feminist issues, as many prior films made by Miyazaki do (including Kiki’s Delivery Service and Princess Mononoke). There is also a strong Marxist context surrounding the director; in 1964 he became the head of the Animator’s Union in Japan, aligning himself with the proletariat as well as with socialist beliefs. It can be argued that Spirited Away is a category C film in Marxist terms, defined by Comolli and Narboni as a film that works ‘against the grain’ stylistically without overtly political content, but that becomes so ‘through the criticism practised on it’. To demonstrate, Spirited Away features an unusual narrative progression that doesn’t obey the Hollywood three-act structure, doesn’t always employ editing techniques that maintain continuity, and includes Japanese imagery not explained for the dominant Western audience. These formal features imply a deeper layer of Marxist meaning in the work, that come to light through close scene analysis and juxtaposition with a feminist reading.

By looking at the premise and plot of Spirited Away, particularly the characters, story, and setting, concerns subtly or overtly put forward regarding class and gender can be identified. The film begins with Chihiro, a grouchy ten-year-old girl, stumbling upon the spirit world with her parents, who are turned into pigs for stealing the food of the spirits. She then must work in a bathhouse as a cleaner with other women in order to gain her freedom and turn her parents back into humans. Rather than working her way up through the ranks of the bathhouse, as a more individualistic and capitalist film may have positively depicted, Chihiro is focused on survival – she must regain her basic human rights through hard labour. Those who work in the bathhouse must perform this labour to even be recognised as valuable, reflected in the fact that those who don’t are turned into animals and considered lower forms of life. This situation reflects critical concepts surrounding capitalism, particularly that those without institutional wealth must work harder to gain any kind of respect.

Similarly, the more subtle feminist concerns of the film can be seen through Chihiro’s character, specifically her design. Rather than having large eyes and upbeat mannerisms as is typical for female characters in other Japanese animations (like Sailor Moon from her titular series), she has small features and a sullen expression, as well as a lanky and boyish frame. This prevents the character from being sexualised, as does the fact that much of the film is from her perspective, utilising low angle shots and close-ups to indicate her loneliness in an unfamiliar world. All of this reflects Laura Mulvey’s notion of ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’, an attribute Chihiro does not possess; as well as her concept of ‘the male gaze’, which is subverted by Chihiro’s feminized perspective. This androgyny is further emphasised by the appearance of her friend Haku, who is animated with more graceful movements and has more conventionally feminine and attractive features, for instance, a pointed chin and large eyes.

The watercolour backgrounds of Spirited Away that the celluloid animation takes place over feature run-down buildings designed with a Shinto appearance like shrines. This relates to the Japanese religion that values natural phenomena, and spirits that inhabit often mundane objects, also embodied in the film by the many Gods that visit the bathhouse, like the Radish Spirit and the River Spirits. However, this appearance is also used by Miyazaki to criticise the capitalist attitudes adopted by the bathhouse. Upon their arrival to the spirit world, Chihiro’s father comments that the buildings are ‘fake’, and likely belong to an ‘abandoned theme park’. This suggests that the Shinto appearance disguises a more modern, and perhaps less authentic way of thinking about the world, capitalist and individualist ideas in particular.

Though in charge of an ancient Japanese institution, Yubaba is more interested in gold and monetary gain than the community of the spirits, as exemplified by her disgust at what is believed to be a ‘Stink Spirit’ but is actually a polluted River Spirit. This also brings in environmentalist themes (common to Miyazaki’s work) that imply the consumerism of the bathhouse and of the world at large is negatively influencing the environment, considered sacred within the Shinto religion. Chihiro’s family car is a four-wheel drive filled with luggage, and upon their arrival at the bathhouse, their guzzling and swallowing of the food seem intended to elicit disgust, dominating the sound design. This suggests a modern fixation on property and consumption that ultimately causes damage to both the unhappy Chihiro and the environment. This reading is even reflected in the cut flowers that she receives from a friend, removed from the Earth and beginning to wilt, her need to receive a floral gift has actually caused more harm to nature, and only made her greedier in turn.

In terms of intersectionality, Chihiro represents the lowest class in both patriarchal and capitalist structures as a young girl employed as a cleaner. Yubaba, a witch representative of the bourgeoisie, states that she will give the begging Chihiro the ‘hardest’ job she has, and Chihiro is later shown participating in physical labour such as scrubbing the floors and filthy bathtubs of the upper classes (the spirits and Gods). The size of these Gods is highlighted by the bombastic music and wide, low angle shots employed when they are onscreen, contrasting with how Chihiro is often described as ‘puny’, wearing oversized clothes not intended for her. While Chihiro works and lives with a group of only women, other groups at the bathhouse with different occupations are shown to be of the same species and primarily interact with others of their kind. For instance, the men resembling frogs managing the front desk of the business. This visually depicts a rigid class structure in which some individuals are given greater institutional power from birth according to their background, a privilege Chihiro is not afforded as seemingly one of few humans there. Even the physical structure of the bathhouse gives a sense of the class structure within; Chihiro initially enters and begs for a job in the basement, with Yubaba lives on the highest floor.

After she begins work with these women, a montage depicts the work they take part in, such as cleaning the floors in unison, resembling a mechanism that Chihiro cannot keep up. This moment indicates how the bathhouse values work over the workers; as Chihiro is unable to fit into the machine, she is seen not only as a non-valuable person, but her identity as a capable female is made more insecure. Her feminine identity amongst the women is also brought into question when her name is stolen and changed to Sen by Yubaba – whereas Chihiro is an exclusively feminine name, Sen is more androgynous.

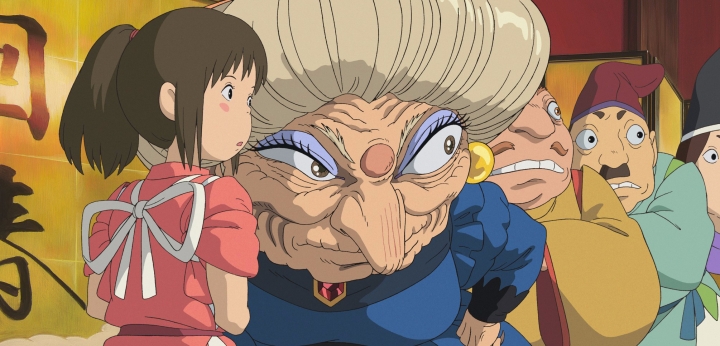

Serving as the main antagonist of the film, Yubaba is one of the more complex and interesting figures in Spirited Away. As both the owner and boss of the bathhouse and a powerful witch, Yubaba is positioned as the most formidable character in the film, with both the most wealth and the most magical potency. Her office is shown to be full of jewels and other valuable artefacts, hoarded for no discernible reason aside from her greed. Therefore, it can be interpreted that she stands as a figure of postfeminism, usually defined as the notion that feminism is no longer necessary, and that women can be successful within capitalism; she herself has attained more capital than any other character, male or female. As Yubaba is symbolic of this ideology, it stands to reason that Miyazaki is criticising it by positioning her as Chihiro’s tormentor and generally portraying her as a cruel and selfish character. Rather than assisting other women or attempting to fight existing power structures, she has reached the top of the hierarchy herself and continues to subjugate others who have not. The only weakness she is shown to have is the care she must provide for her baby, who dominates her with his unnaturally large size – this could be seen as a metaphor for how she is still affected by the gender expectations of capitalism and patriarchy, despite her monetary success.

As both feminist and Marxist frameworks position themselves as critiquing the dominant ideology (patriarchy for the former and capitalism for the latter), it can be theorised that much of Spirited Away serves to criticise these ideologies and how they are enforced. This is achieved most effectively by the enigmatic, well-beloved character of Kaonashi or ‘No-Face’, a being who begins as a blank slate and gradually becomes corrupted by the principles surrounding them in the bathhouse, serving as a representation of the power of dominant ideas. Their design reflects this concept: they are black and formless at the start of the film with no visible limbs, the mask they wear giving a neutral expression and concealing any facets of identity, such as gender, age, or class. At the beginning of the film, they are only capable of grunts, suggesting that they don’t have the knowledge at their disposal to form words and sentences, and further reinforcing the notion of them as a being uncorrupted by any kind of outside influence.

However, when they come across a male frog creature, they lure him using gold – appealing to his notable greed – and swallow him, gaining his capitalist, male attributes. This is an allegory for how ideology influences unassuming and otherwise innocent individuals, leading them to commit cruel acts due to misguidance, and turning the character into a symbol of greed and excess. Kaonashi continues to devour different creatures from the bathhouse, becoming increasingly large and proclaiming that he will “eat everything”, growing into an almost secondary antagonist for the film. This is put to a stop by Chihiro, who gives them food that forces them to regurgitate the people they have consumed, returning them to their original state. Continuing the allegorical reading, this can be seen as someone from a lower societal position showing them the injustice of the system, bringing them to a greater awareness – as reflected in their moderate consumption of food with female characters later in the movie.

Spirited Away tends to be lauded for its beautiful, detailed environments, bizarre imaginative imagery, and memorable characters. But beneath this runs an undercurrent that also deserves appreciation: as a masterpiece of feminist and Marxist storytelling, the film stands not just as a monument of 2D animation, but as a thoughtful and insightful look at how the intersection of class and gender can determine so much about your experiences.

by Zoe Crombie

Zoe Crombie is a film student from Lancaster who can usually be found eating spaghetti and watching movies from one of the following three categories: Studio Ghibli, Marx Brothers, and camp horror. You can follow her on Twitter at @CrombieZoe and keep up with her work at her blog obsessreviews.com

Zoe Crombie is a film student from Lancaster who can usually be found eating spaghetti and watching movies from one of the following three categories: Studio Ghibli, Marx Brothers, and camp horror. You can follow her on Twitter at @CrombieZoe and keep up with her work at her blog obsessreviews.com

Categories: Feminist Criticism

1 reply »