Seeking escapism and a nostalgia for when we could all be in the same room together, I was captivated by The National Theatre at Home’s screening of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Staged in the round, it was like watching a riotous summer party unfold, filled with glittering acrobatic fairies, impromptu dance numbers and even Beyoncé’s “Love on Top”! It was set in a familiar yet strange dream world that was born out of entwining today’s technology and culture with fairy tales and make believe. Hilarious, joyous and magical, it was one of the most original and exciting adaptations I’d ever seen of any Shakespeare play. It was a reinterpretation of classic material fiercely undaunted by the reputation and history that often swallows up modern adaptations of Shakespeare’s work. This fearlessness ultimately made for something truly unique and surprising.

Baz Luhrmann also famously achieved this with his ground-breaking modern day Venice Beach, Radiohead-infused adaptation of Romeo + Juliet in 1996; drawing parallels between Elizabethan violence and modern day gang wars as well as the enduring idea of young love that has transcended centuries. He managed to make Shakespeare sexy, but it wasn’t only because of young Leonardo DiCaprio. Luhrmann managed to find things within these ancient plays that would still enthral and delight audiences today. We’ve grown acclimatised to brutality, scandal, power and sex – we talk about these things every day and see them on screens everywhere. However, given the extent to which Shakespeare’s plays also explore these themes, it can be said that he was playing to what audiences of the time also wanted to see. Ultimately, these themes are still ever present in our storytelling as they fuel our curiosity and desire to see our world reflected back at us so we may better understand it, both past and present.

In light of this, I wanted to explore visionary writer/director Julie Taymor’s visceral admiration of Shakespeare in her reimagining of Titus and The Tempest. Her style of filmmaking is distinctively theatrical and full of dazzling spectacle, no doubt influenced by her extensive background and training in the theatre. She ultimately utilises this signature visual flamboyance to stylise and expose the innate truth of the human condition with arresting originality; unearthing today’s world from within Shakespeare’s work with masterful beauty, perceptiveness and imagination. As actor Harry Lennix said of Taymor, “In her work, she taps into the shadow side of all of us and sometimes she taps into the divine. What distinguishes her from other gifted directors is how she combines the two and lets you see how both of those roles co-exist within all of us.” If you’ve seen any of her films, you’ll know it’s no stretch for me to deem her a genius, and here’s why…

One of Shakespeare’s earlier works, Titus Andronicus, a revenge tragedy, is notable for being one of his most shockingly sadistic and darkly humorous plays. Throughout, we watch as an epic conflict between Titus (Anthony Hopkins) and Tamora, Queen of the Goths (Jessica Lange), unfolds, simmering below the surface and then erupting in gory redemption time and time again as a war is waged in the name of an eye for an eye… and then maybe a hand, an arm and even a head or two…

Work began on Titus not long after Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996) was released. The success of the latter arguably reignited an interest in Shakespeare on film and more importantly, the need to revamp the material in order to make it appealing for a modern day audience. The play, Titus Andronicus, is bloodthirsty enough to rival any Quentin Tarantino massacre and can even be seen as precursor to the Sweeney Todd tale; a revenge story of devilish black comedy contrast against truly grisly violence. However, Julie Taymor’s execution of the play on film focussed on stylising the most gruesome aspects of the text, investigating, in her own words, “how beautiful is the grotesque?” She cites this in reference to a strange contradiction in human nature in terms of people’s attitudes towards violence, for example; how can people be disgusted by brutality yet still admire macabre depictions of crucifixion, battles and murder displayed in art galleries around the world?

One of the most supremely disturbing moments in the film is the aftermath of the rape of Lavinia (Laura Fraser), Titus’ daughter by Queen Tamora’s two sons. Her tongue has been cut out and her hands replaced by small tree branches so she may never reveal the identities of the men that did this to her. She is then left standing in the centre of a swamp atop a tree stump when her Uncle eventually finds her. From afar, she appears as an eerie balletic creature, poised elegantly in her ravaged white dress, surrounded by mud and dying trees. As her Uncle draws closer and to his horror, recognises her, she spreads her arms, revealing her new mutilated hands as blood pours from her mouth in a silent scream toward the camera. The nightmarish imagery of this shot is one of the most striking visuals in the film and has remained with me even years after I first saw it. It’s deeply unsettling and not exactly “beautiful”, however, what makes this a stunning shot is how Taymor symbolically elevates Lavinia’s emotions, her trauma being heightened within a hellish, otherworldly image that is emotionally arresting and thus, unforgettable for the viewer.

There is something both monstrous and poetic about the film’s stylisation with Taymor creating an aesthetic that forms something in between Mad Max (2015) steam punk meets the crazed, glamorous debauchery of Moulin Rouge (2001). Taymor also clashes time periods against one another, having chariots, tanks, swords and machine guns all exist in the same anachronistic world, “symbolically depicting over two thousand years of warfare”. Furthering this, the costumes, sets and music all reference different periods of history: modern day, Ancient Rome, Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s fascist Italy to give the impression of the pursuit of power transcending across millennia’s. This is even implicated in the casting of certain roles, for example, Alan Cumming’s charismatic portrayal of the hilariously eccentric new Emperor of Rome, Saturninus. Before filming, Alan Cumming had recently risen to fame for his iconic portrayal of the Emcee in Sam Mendes’ Broadway revival of Cabaret, a musical set in early 1930’s Berlin on the brink of the Nazi’s rise to power. In Titus, Alan Cumming’s makeup and hair styling is kept very similar to that which he wore in Cabaret, perhaps it being Taymor’s intention to subconsciously echo an era audiences already associated Alan Cumming with. Consequently, this highlights the parallels Taymor was trying to draw between violence within this fantasy reality of the film and also our own history. This is also notably captured in the mesmerising and rather distressing opening sequence:

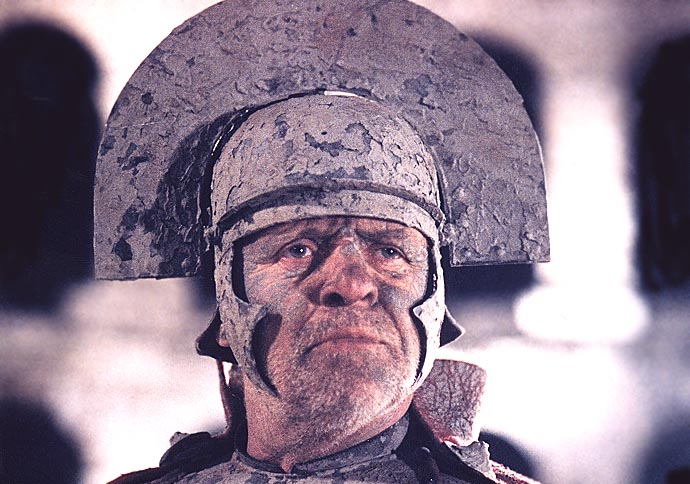

A young boy in a modern day kitchen is shown playing with his toys with the TV on in the background. Gradually, the sound of gunfire, bomb explosions and the whistling of distant missiles fill the room. The boy seems to get influenced by what he hears, as soon he is screaming, smashing plates and hurling food around: savagely drowning his action figures in tomato ketchup like a deranged Sid from Toy Story (1995) in an unnerving descent into culinary carnage. Not long after, he’s whisked away by a Roman Soldier and taken to the Coliseum, greeted by a grey dust covered army (much like the Terracotta army). This is where we meet our protagonist, Titus Andronicus, victoriously returning from battle after defeating The Goths. The sounds of war the boy hears serve as a trigger for transporting him back in time, Taymor suggesting here that humanity’s inherently violent nature connects us all throughout history and emphasises how, in fact, we have evolved very little.

In a twisted fable that magnifies the glorification of the diabolical in our culture today and across time, Taymor conjures a world built from a tapestry of the instant feelings and images evoked when we think of violence. As evidenced by the success of Quentin Tarantino’s work and the fantasy epic Game of Thrones, it’s apparent people still have a guilty appetite for brutality, just as much now as they did hundreds of years ago! I don’t think violence is necessarily the primary draw, nonetheless, it has become a key element of both Tarantino’s work and Game of Thrones: people know what to expect when they watch them and their graphic nature hasn’t deterred their success. However, what I feel ultimately makes Taymor’s Titus unique is that it’s more than just a revenge story, it’s intrinsically about the severe consequences of such a blind pursuit born from extreme grief and rage. As Taymor said, “I love the truth of the play but I can’t stand the reality of it”.

Over a decade after Titus, Julie Taymor embarked upon her second film adaptation of Shakespeare’s work, his final masterpiece, The Tempest. Not only is it considered Shakespeare’s most magical play but also an eclectic culmination of all his greatest work, infusing romance, comedy, tragedy and redemption into a fizzing and fantastically mythic tale. In it, we see the sorceress Prospera (Helen Mirren) exact her vengeance on the Royal Court Officials who usurped her title as the Duchess of Milan and thus left her exiled, stranded on a remote and unruly island with her young daughter, Miranda (Felicity Jones). Twelve years later, Prospera conjures a storm to sink their ship off the coast of her island and here begins her tumultuous pursuit of revenge, manipulating the elements and magical inhabitants of the land to do her bidding.

It’s a story that ruminates on the idea of mortality, man versus nature and magic versus reality. However, in Julie Taymor’s adaptation, it also looks at the theme of the past versus the present, displayed by the bewitching impact of modern visual effects that elevates the awe and enchantment of a classic story. Shakespeare’s heightened language is inherently visual, full of poetic imagery and thus naturally lends itself to film very well. In Taymor’s adaptation, we’re truly invited into the world of The Tempest, the textured landscape of the volcanic black sands, rich forests and furious seas offering a more amplified experience of the text.

Having said this, the special effects used in Taymor’s adaptation perhaps aren’t the slickest, no doubt due to a relatively small budget. Nonetheless, the inventiveness of the style she uses arguably lends an even more magical, otherworldly quality to these moments. At times they are even stylistically reminiscent of the early films of George Méliès, as we see the spirit, Ariel, moving in a kaleidoscopic dance within the stars, the blue hue of his skin tinged with flames as he sets King Alfonso’s ship ablaze.

Ultimately, Taymor saw the smaller budget as an opportunity to think creatively, consequently making for some truly imaginative results. For example, one of the most whimsical effects in the film are the shots of Ariel (Ben Whishaw), inspired by Brian Oglesbee’s photography using water over glass. This created a stunning distortion of Ariel’s face by also projecting landscapes onto the water and over his features, truly making it seem as though he were engrained into the natural elements. The Tempest is also mesmerising in its use of more practical effects, such as make-up, a notable scene being the transformation of Ariel into a malevolent ‘harpy’, his face and enormous feathered wings dripping in black oil as he drives the Royal Court Officials mad during a terrifying incantation scene. In these effects, Taymor avoids predictability and creates magic onscreen that is surprising and often breath-taking in its beauty and originality.

The magic was also heightened by the score, sometimes using heavy metal and hard rock inspired themes during these sequences to emphasise Prospera’s sorcery is not of the Jacobean world and is in fact, timeless, calling on our own modern day music to signal this to the audience. This also adds to Taymor’s casting of Ben Whishaw who plays Ariel, who described him as looking like “a young Keith Richards” in the “Raising the Tempest” DVD Featurette. The ethereal and androgynous appearance of Arial also echoes David Bowie, this resemblance no doubt being due to his snow white tan and chameleonic ability to shapeshift into whatever he pleases. Furthering this, Taymor proceeded to draw parallels between today’s comedians and the comics of Shakespeare’s time by casting Russell Brand as Trinculo, the Royal Court Jester! Known for being particularly witty and eloquent, this made Brand a perfect choice for the role as it enhanced the applicability of the text to modern day by making the humour more identifiable. Taymor emphasised this by pointing out, for seventeenth century Court Jesters, “no one is too sacred to make fun of and that’s exactly what Russell does!”

However, the casting choice that makes Taymor’s adaptation of The Tempest more distinctive than any before it was the changing of the protagonist’s gender from male to female: from Prospero to Prospera. Legendary Helen Mirren played the lead role and this was accomplished in such a way that not only refrained from being gimmicky but even elevated the complexity of the story, providing a revamp for a modern audience that are keen to see more strong female leads onscreen. Ultimately it also lent a refreshing maternal dynamic, not only to the character’s relationship with Ariel and her daughter, Miranda, but also by honouring the eternal association that women have with the land, encapsulated by the very term, ‘Mother Nature’. In Shakespeare’s original play, Prospero, as a man, is seen to dominate Mother Nature, manipulating the elements for his own personal gain. However, in Taymor’s version, this is subverted and feels more empowering in the way we see a woman take control of her surroundings, being at one with the natural world as all her magic is conjured from the land itself.

However, in spite of this, the character of Prospera is far from being a wholly admirable figure. Themes of racial divide are extremely pronounced in The Tempest, as demonstrated by Prospera’s hostile treatment of her slave, Caliban, who was originally born on the island. This has subsequently been perceived as Shakespeare’s comment on Britain’s unrelenting colonisation of the world and the thriving slave trade of the era, “I am subject to a tyrant. A sorceress that by her cunning hath cheated me of the island”. This is amplified in the make-up design for Caliban in the film, as Jacobean insults have been carved onto his stomach, presenting themselves as raised scars on his skin, as though he were the property of Prospera, and thus, a culture alien to him. This detail Taymor imbues highlights the trauma of the character having his identity violated and his home overtaken by an intruder. Infuriatingly, racial prejudice is still prominent today and thus the dynamic between Caliban and Prospera is an imperative relationship to illustrate to modern audiences.

Finally, Taymor’s The Tempest also makes a chilling statement about humanity’s impact on the environment. Despite Prospera’s gentle and doting relationship with Ariel, she still refuses to discharge him from her service until he has upheld her every command, thus manipulating nature to serve her own desires. We, as human beings, have been guilty of doing the same; enslaving and reaping the resources of the Earth for our own needs. Although there’s mutual respect and admiration between Prospera and Ariel, he still longs for his freedom above all else and there is an arrogance about Prospera, essentially an invader of the island, in assuming that Ariel owes her his service, and moreover that nature is at her disposal. No doubt it was Taymor’s intention to mirror this with our own selfish desires to control the seas, shores and even the stars.

Overall, Shakespeare’s plays will always be relevant, but it takes a true visionary like Julie Taymor to daringly reimagine them, ultimately offering a fresh insight into our world that justifies the need for their return to our stages and screens. Storytelling is one of the most powerful catalysts for inciting change, and in Julie Taymor’s passion and commitment to reviving Shakespeare’s work, we have a portrait of who we’ve always been, and hopefully, who we might become.

by Angel Lloyd

Kadija Osman @kadijaosman_

Kadija Osman is based in Toronto, Ontario and is currently completing her undergrad in journalism at Ryerson University. She enjoys writing about film and TV. When she isn’t watching Timothée Chalamet’s filmography, she is probably reading romance and thriller novels or ranting about the disappointing cancellation of E!’s The Royals. Her favourite films include Kingsman: The Secret Service, Lady Bird and Ready or Not. You can find her on Twitter: @kadijaosman_ and Letterboxd.

Carmen Paddock @CarmenChloie

Carmen is a Pennsylvanian transplant to Glasgow who writes about film, television, and opera. A lover of maximalism and musicals, much of her writing focuses on cross-media adaptation. Favourite films include West Side Story, 10 Things I Hate About You, Ludwig, Cabaret, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, and Moulin Rouge!. She holds a Masters in International Film Business from the University of Exeter / London Film School. Follow her on Twitter @CarmenChloie

Leave a comment